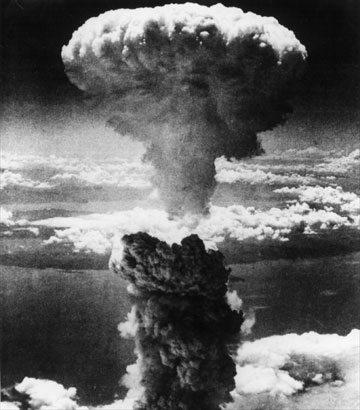

Seventy years ago today, the United States dropped an atomic bomb – laughingly called ‘Little Boy’ – on the Japanese city of Hiroshima and three days later they dropped a second device on the city of Nagasaki.

The two bombings killed around a quarter of a million people with roughly half dying in the immediate aftermath of the explosions and half taking longer to die of starvation, lingering physical injuries and most horrifyingly of all, radiation sickness.

The justification for using weapons of such horrifying power has always been that they brought about the end of the Second World War and resulted in fewer net deaths than forcing the end of the war by conventional means. Of course, this ignores the probability that Japan would have accepted a conditional surrender right then and would have been even more likely to do so once Russia joined the war in the Pacific.

As such, the desire to obtain an unconditional surrender, alongside the preference to keep the Russians out of the picture in the East must play into the justification for using the bomb. It must also be considered that the United States wanted a live test of their new weapon (as in, on a city with people in it rather than just some desert in New Mexico) and to lay down a marker for the looming confrontation with the Soviet.

Even the scientists who first developed the bomb petitioned the US government and military that it not be used in anger, with Robert Oppenheimer’s oft quoted reminiscence of Hindu scripture capturing the essence of those scientists feelings – “I am become Death, destroyer of worlds.”

Ever since, the existence of nuclear weapons has been justified by insinuating that they are instruments of peace, firstly for being the full stop that ended the Second World War and then by precluding the possibility of a conflict between major powers as none would be so fanatical as to risk a nuclear conflict with it’s natural climax of mutually assured destruction.

The thing is, those old justifications just don’t hold water anymore.

The world has changed since 1945, or even since the most celebrated flashpoint of the Cold War, the ‘Cuban Missile Crisis’ in 1962 where nervous fingers hovered over the nuclear launch button as Russia and the USA stared each other out off the coast of Cuba.

Russia is not the power it was in the 60s, China has arguably caught up with the United States as the world’s dominant economy (and military force), Europe is more united than ever and new powers like India are flexing their muscles on the world stage. Even so, none of the major powers are the biggest threat to world peace as religious fundamentalism, rising issues of inequality, hunger and climate change threaten to destabilize nations from the bottom up, fuelling desperate migration and terrorism.

There is no serious nuclear threat to the UK from a major nation, no matter how much some people might like to scaremonger about Vladimir Putin or China’s imperial ambitions. None of the nuclear powers will use their weapons against each other (or anyone else for that matter) knowing that at least one other power would respond in kind. Do we really think that if we gave up our nukes, we’d be annexed by Russia or that we’d be powerless against the whims of France & Germany?

The military threat to the UK comes from terrorism and all the nuclear submarines in the world will not protect us from small groups of desperate, stateless people who believe they are enacting the will of a higher power or in the name of a greater cause.

As such, the possession of nuclear weapons does not make us safer but rather provides a target with apocalyptic implications should it ever be successfully attacked.

In truth, the proposed renewal of Trident is more about giving business to preferred contractors and our nation’s leaders feeing like we are a world power in possession of a metaphorical ‘big stick’ to lord over smaller or less developed nations and to use as a crutch for credibility when dealing with genuine powers.

In light of this country’s economic issues, rising inequality, the cuts to the welfare state and the selling off of public services, the prospect of spending billions of pounds (around £25 billion to obtain the new system and a total of £100 billion to maintain the weapons and their delivery systems for the proposed 40 year lifespan) on weapons which are effectively useless, dangerous and morally indefensible is surely anathema to any decent, compassionate person?

I look up the Clyde today, to where Britain’s own nuclear arsenal makes its home and I shiver. The thought of the destructive capability of those missiles and all that they stand for terrifies me. The knowledge that those warheads are transported in convoy through Glasgow, within a mile of my home on a regular basis almost brings me out in a cold sweat.

It’s not just fear for what might happen if there is an accident or a successful terrorist attack on Faslane or those convoys, but a deep seated horror that I belong to a country which thinks it is acceptable to own, house and threaten to use such weapons.

It’s time to give up on being a nuclear power. It’s time to address the economic and social issues which are ripping Britain apart at the seams and take responsibility for the global inequality which fuels the migration and terrorism which are our biggest international concerns.

Scottish Fiction

It isn’t in the mirror

It isn’t on the page

It’s a red-hearted vibration

Pushing through the walls

Of dark imagination

Finding no equation

There’s a Red Road rage

But it’s not road rage

It’s asylum seekers engulfed by a grudge

Scottish friction

Scottish fiction

It isn’t in the castle

It isn’t in the mist

It’s a calling of the waters

As they break to show

The new Black Death

With reactors aglow

Do you think your security

Can keep you in purity

You will not shake us off above or below

Scottish friction

Scottish fiction